Why quality improvement needs both discipline and human judgment ?

In quality and process improvement, we teach a simple idea: standardize the work.

It’s a powerful principle. Standard work reduces variation, improves reliability, and makes outcomes more predictable.

But in healthcare—and in most complex environments—there’s a second truth that matters just as much:

Reality doesn’t always match “standard conditions.”

So the mature improvement mindset isn’t “standards versus judgment.”

It’s standards + judgment + learning.

This is where the phrase “break the rule” comes in. Done poorly, it sounds like permission to ignore standards. Done well, it means something very different:

Use standards as the default, and use professional judgment when the situation demands it—then convert every deviation into learning.

Why standards exist (and why they’re non-negotiable) ?

Standards are not bureaucracy. They are an agreement on the best known way today to deliver safe, consistent outcomes.

Standard work helps us:

- Protect safety (patients, staff, operations)

- Reduce variation (so results are repeatable)

- Prevent rework (less waste, fewer delays)

- Expose problems (deviations become visible signals)

- Improve faster (a stable baseline makes improvement measurable)

Without standards, improvement becomes opinion-driven.

With standards, improvement becomes evidence-driven.

The problem: standards are designed for the “normal case”?

A standard is usually built around assumptions:

- inputs are available (people, equipment, information)

- the patient or case fits typical patterns

- the environment is stable enough to follow the sequence

- risk is within expected boundaries

But healthcare is a living system. Risk changes quickly. Demand surges. Resources fluctuate. Patients don’t read our policies before arriving.

When the real world shifts outside the assumptions, a standard can become:

- unsafe (the “right step” at the wrong time)

- impractical (impossible to follow due to missing inputs)

- ethically conflicting (compliance competes with patient-centered care)

This is why strict compliance alone is not the definition of quality.

Quality is outcomes, safety, and reliability—achieved through disciplined systems and sound judgment.

“Breaking the rule” is acceptable—when it protects the intent

Here’s the most important distinction:

Robots follow rules. Professionals follow intent.

The standard has an intent: safety, quality, fairness, timeliness, reliability.

If a step must be adapted to protect that intent in an unusual scenario, adaptation can be appropriate.

But there are only a few defensible reasons to deviate:

1) Safety-critical situations

When following the standard as written increases harm or delays life-saving action.

2) Time-critical situations

When the system’s pace is slower than the risk in front of you, and delaying to “stay compliant” makes outcomes worse.

3) Ethical conflicts

When rigid compliance produces an unfair, harmful, or clearly inappropriate outcome for a specific case.

4) System constraints (work made impossible)

When you cannot follow the standard because a prerequisite failed (missing supplies, downtime, staffing gaps, broken process handoffs).

This last category is especially important in improvement work:

Many “rule breaks” are not people problems. They are signals that the system didn’t support the standard.

The danger: breaking the rule for convenience (and hiding it)

Not all deviations are equal.

Deviations are not acceptable when they are:

- convenience-based (“this is faster for me”)

- habitual (“we always do it this way”)

- hidden (no escalation, no documentation, no learning)

- risky without mitigation (no check, no backup plan)

A culture that normalizes quiet workarounds becomes fragile:

- risk grows silently

- variation spreads

- bad practices become “how we do things”

- leaders lose visibility into real constraints

- improvement stalls because the system never sees the truth

The professional approach: adapt with controls, not freestyle

In mature organizations, deviation isn’t random. It’s managed adaptation.

If you must deviate, do it with controls:

- Add safety checks (second-person verification where needed)

- Communicate early (handover, escalation, situational awareness)

- Document appropriately (especially where clinical/legal requirements exist)

- Use the lowest-risk workaround that preserves the standard’s intent

- Return to standard as soon as conditions allow

This protects patients and protects staff—because it turns “I improvised” into “I made a controlled decision.”

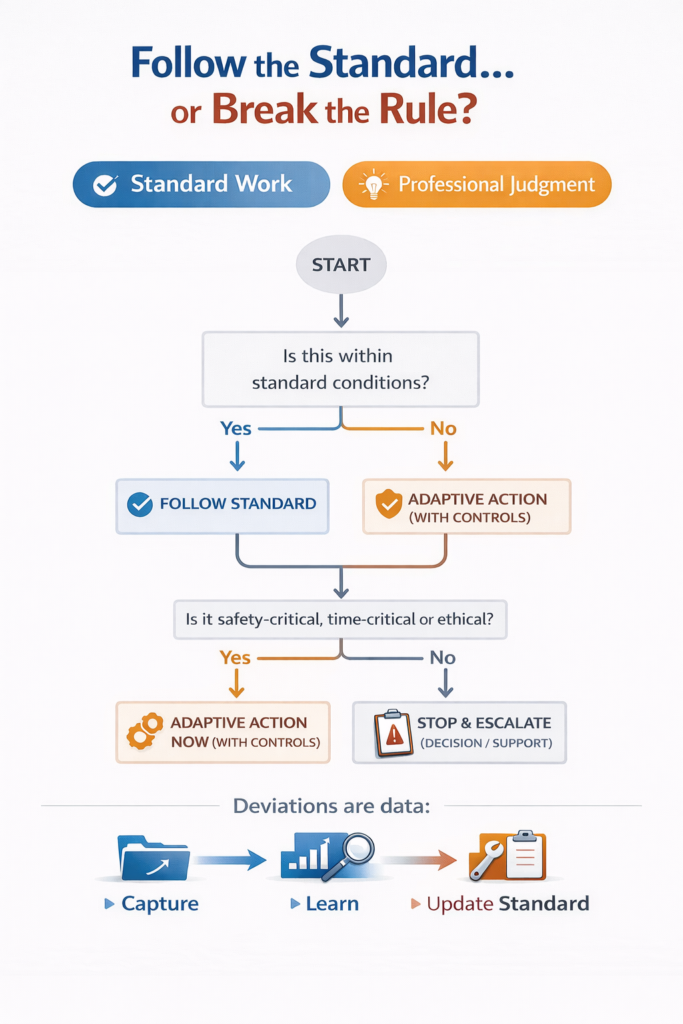

A simple decision guide (that makes this practical)

You can think of it as two questions:

Question 1: Is this within standard conditions?

- Yes → Follow standard work

- No → Go to Question 2

Question 2: Is it safety-critical, time-critical, or ethical?

- Yes → Adaptive action now (with controls)

- No → Stop and escalate (get decision/support)

This prevents two common failures:

- blindly following a standard when the situation is unsafe

- silently improvising when the situation is not urgent

The improvement engine: deviations are data

The most powerful line in this whole concept is:

Don’t hide deviations. Learn from them.

Every deviation should trigger learning:

- Capture: What happened? What condition forced the deviation?

- Learn: Why didn’t the standard fit? What failed around it?

- Update: Improve the standard, training, resources, or environment

This is how standards stay alive.

Standards should not be treated as a permanent truth. They are version 1.0, 2.0, 3.0… evolving with reality.

The leadership message that changes culture

If leaders only reward compliance, teams will hide the truth.

If leaders reward learning, teams will surface reality.

A healthy culture says:

- “Follow the standard by default.”

- “If you must deviate, do it safely and transparently.”

- “And tell us—so we can fix the system.”

That’s how you build reliability without turning humans into robots.

Standards create consistency.

Judgment handles complexity.

Learning turns exceptions into better systems.

The goal isn’t perfect compliance.

The goal is safe, reliable outcomes—delivered by people who think, adapt, and improve.

Organizational Entropy: Why “Closed Systems” Quietly Collapse