A Lesson in Systems Thinking

In the high-pressure world of healthcare management, the mandate is almost always the same: Do more with less. We are constantly looking for efficiencies, cutting fat, and optimizing budgets. But this isolated approach often ignores the principles of systems thinking, leading to a dangerous trap. It is the belief that if every department saves money individually, the hospital saves money collectively.

This is a myth. And to prove it, let me tell you the story of the “Cheaper Sterile Gloves.”

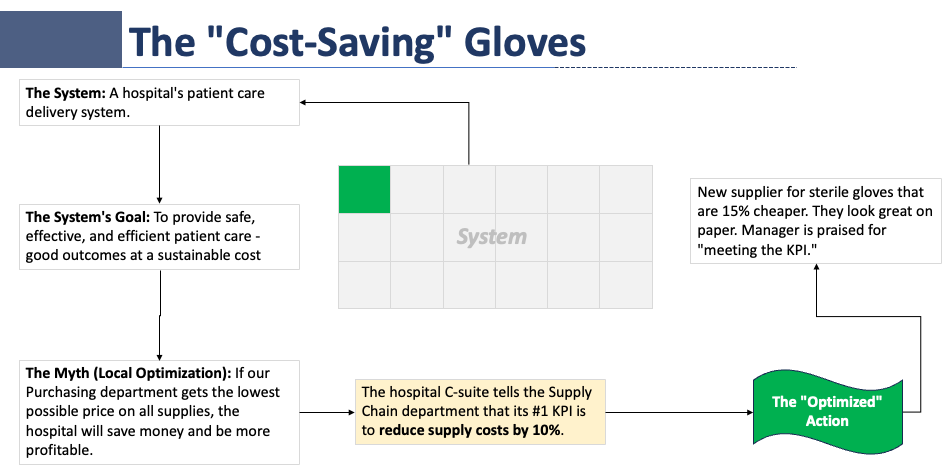

The Trap of Local Optimization

Imagine a hospital Supply Chain Director. Let’s call him Mark. Mark is a good employee. His annual Key Performance Indicator (KPI) is clear: Reduce supply costs by 10%.

Mark analyzes his spreadsheets and finds a golden opportunity. The hospital currently spends millions on sterile surgical gloves. He finds a new vendor offering gloves that are 15% cheaper than the current brand. On paper, the specs look identical.

Mark does the math. This switch will save the hospital $250,000 a year. He signs the deal. He hits his KPI. He gets his bonus. The Finance department is thrilled.

Mark has successfully “optimized” his part of the system.

The Ripple Effect

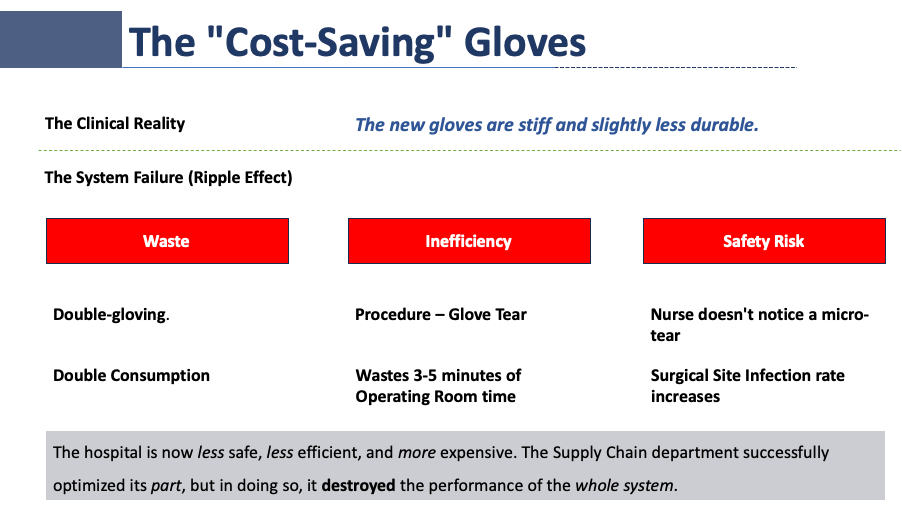

Two weeks later, the new gloves arrive in the Operating Room. The reality of the “system” begins to push back against the spreadsheet.

The new gloves are slightly stiffer and have a lower tensile strength. They are “good enough” for standard exams, but they struggle under the rigor of orthopedic surgery.

Here is what happens next:

- The Waste (The $10 Loss): Nurses notice the gloves tear when they pull them on. They throw away the torn pair and grab a new one. Suddenly, the hospital is using two pairs for every one procedure. The 15% price reduction is instantly wiped out by a 100% increase in consumption.

- The Delay (The $1,000 Loss): A neurosurgeon is in the middle of a critical spinal fusion. A glove tears. The procedure stops. The surgeon must step back, scrub out, and re-glove. The patient is under anesthesia for an extra 10 minutes. At an estimated cost of $60-$100 per minute for OR time, that “cheap” glove just cost the hospital nearly $1,000 in lost time.

- The Risk (The $10,000 Loss): In the rush of the ER, a micro-tear goes unnoticed. A post-operative infection develops. The patient is readmitted. The hospital absorbs the cost of the readmission and the penalties.

The Supply Chain department saved $250,000. But the Clinical Operations department lost $1,000,000 in overtime, waste, and readmissions.

The hospital is now less efficient and more expensive.

The Core Principle: Interaction vs. Isolation

Why did this happen? It happened because we treated the hospital as a collection of separate parts, rather than a system of interactions.

As the systems thinking pioneer Russell Ackoff famously said:

“A system is never the sum of its parts; it’s the product of their interaction.”

When we optimize one part in isolation (Supply Chain), we often de-optimize the whole (Patient Care). This is called Local Optimization. It is the enemy of system health.

In a complex system like a hospital, the cost of a product is not the price on the invoice. The true cost is how that product interacts with the nurses, the doctors, the patients, and the processes.

The Solution: Sub-Optimizing for the Whole

So, what is the alternative?

True Systems Thinking requires us to sometimes sub-optimize a part to improve the whole.

In our story, the correct decision would have been for Mark to buy the more expensive gloves.

- His department’s budget would look “worse.”

- He might miss his 10% savings KPI.

- BUT: Surgeries would flow smoothly, waste would drop, and infection rates would stay low.

To fix this, we need to break down the silos:

- Change the KPIs: Don’t reward Supply Chain solely for “price reduction.” Reward them for “Total Cost of Care.”

- Value Analysis: Purchasing decisions should never be made in a boardroom without a clinician present. The people who use the system must validate the parts.

- Look for the “Product”: Before changing a variable (like a glove, a drug, or a staffing ratio), ask: How will this interact with the next step in the process?

Conclusion

A hospital is not a factory of independent assembly lines. It is a living organism. When you pinch one vein, the pressure rises somewhere else.

The next time you are presented with a way to “save money” in one department, stop and ask the uncomfortable question: “If we optimize this part, what are we destroying in the whole?”

Sometimes, the most expensive glove is the cheapest one to buy.